Recently, a friend posted a shocking status update on Facebook… she checked into an airport hotel with a colleague while on a business trip and when the co-worker got to her room, she found a professional cleaning service inside tidying up the bathroom. She jokingly asked, “what, did someone die in here?” And, to her dismay, the cleaner said “yes” and that “it happens about once a month – mostly suicides.” This left me really unsettled.

My dad took his life in a public park, likely as not to create a scene for anyone to clean up or to limit the people who might have been exposed to his act. (But really, who knows why?) I never really thought about the prominence of people doing this in a hotel room before. I’m not sure why, but I decided to Google “hotel suicides” afterward and was flabbergasted by the amount of news coverage on this phenomenon. It’s just not something you hear about – or at least I hadn’t. I imagine the industry works rather hard to keep incidents under the rug. And, maybe as a survivor, I’ve been so wrapped up in the way my own situation occurred that I never really thought about what other families have uniquely experienced.

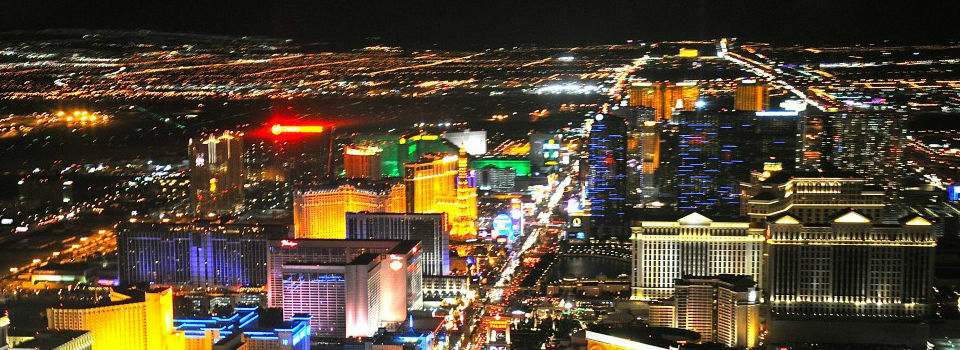

Something that struck me in particular was an article from CBS News about the frequency of hotel suicides in Las Vegas. Experts equated it to the anonymity of the place, as well as the potentially failed attempts of many to recover from financial losses there. Of course, I was immediately saddened by the thought of this. (That goes without saying.) But, what was more interesting to me were the quotes that surfaced.

I was really angered by the aloofness on the severity of this issue by one hotelier. It seems many there just accept this as something that happens.

“A MGM Mirage senior vice president for public affairs said saving people who are suicidal once they arrive at a hotel is probably impossible. ‘If a person’s closest friends and family can’t prevent it,’ he said, ‘How is the bellman at the hotel all of a sudden going to have this miraculous cure? I don’t know if there is very much we can do.’”

I think many survivors would agree this is ridiculous. As did a representative from a local suicide prevention organization. Her suggestion was to put a crisis number on the phone or another area of the room, among others. She also said that all it can take sometimes is for someone to be acknowledged and shown they matter. Maybe a subtle wave, a hello, or a “How are you doing? Is everything ok?” might help. I have read in other places before that someone may have stopped themselves from taking their life after someone simply smiled in their direction – that’s all they needed that day. It’s also unfair to suggest that friends and family are the first and only line of defense since many of us had no idea this was on our loved ones’ minds. Maybe they didn’t want us to know, but there’s a chance that an intervention elsewhere might have helped – we’ll never know the answer.

The article went on to state some of the physical things hotels do to try and stop this, from keeping windows locked to limiting access to rooftops, etc.

This all got me to thinking about how much control we or other third parties really have when someone has arrived at this decision. I think we should all make every effort we can to try and prevent suicides in any situation and not just accept them as something that “happens.” I equate the above sentiments to someone who has never experienced a suicide in their family and is responding from a true business perspective. It’s a shame, really. It would be great if employees of high-risk locations/businesses, bridges, etc. took some sort of awareness course (or it could be part of their job training) to keep an eye out for people who may appear despondent and know what kind of measures to take (e.g. ask if they are ok, hand them a card with a hotline on it, call police, etc.). I know this is a lofty suggestion but it’s wishful thinking on my part that even one more life could be saved by more people paying attention and taking the risk of suicide seriously.

Image from travelandstories.com.